The best divisions are purely fictitious. No story is accurately told in parts, though that is how they’re best told. In reality, there are no clear dividing lines in life, we make them up—not because we’re dumb, but because we’re smart. We make them up because we have to.

The human brain, even the best of them, can only picture (up to) seven things at once. You can picture five apples easily enough, but how about eight? Likely, you’re picturing two sets of four. Fifteen apples can be seen only by picturing three sets of five, but if you try putting those apples in disarray your mind loses track.

We divide things up because it allows us to circumvent our mental limitations. Humans think in parts, even if thinking in systems is more accuratebecause we can’t think in systems. Thinking in parts is a shortcut, a flawed one, but it’s one that allows us to keep track of more apples, measure large-scale productivity, diagnose problems faster, place blame more easily, live life more efficiently, and tell stories.

I guess my story in Bristol would start with me running through the streets of London trying to find the right part of the Victoria Coach Station so I could board my bus to take me down to Plymouth. I would probably have to cut the part about the German girl running with me, my traveling romance, and how the late night we had in Soho, which caused us to miss the last train back, made for a late morning this morning, causing this frantic dash through Westminster.

Or I might place the dividing line at the bus, which I got to in the nick of time, completely out of breath. This would be a good start, but it doesn’t allow me to show the pattern of barely-making-it that defines my travels, like how a week earlier I made my layover in the same way. Regardless, it’s a good start.

The coach was cramped, the seats pressed together so tight I was gnawing on my knees for the eight-hour ride. It smelled like potato peels, but damper. The ride was so bumpy that placing your head against anything was liable to give you a minor concussion if not several. This is what you get when you spend twelve-pound for a two-hundred-mile trip.

Since I only had 2G reception in Europe my phone was little more than useless in the British countryside, and I couldn’t read due to the jostling. With the little reception I had, I managed to find a small hostel that had vacancies, but which only booked rooms over the phone. Unable to call, I resolved that I would just book a room when I got there. Aside from that, the rest of the ride was left to thinking.

I had a lot to think about. Plymouth is not a commonplace for travelers to visit. It’s out of the way, small, with little to do. The reason I was going was to see my birth-sister. We met a few times before, messaged occasionally, and emailed back and forth briefly when we were teens. Despite that, I was incredibly nervous. This was my first time to really be a big brother, here, in a place I knew nothing about.

My experience in London gave me some confidence. Things had worked out incredibly well there, despite a similar lack of planning, and maybe that would happen again? I doubted it but hoped. In London the stakes were low, I only had myself to look out for, but now the stakes were far higher.

This felt like the culmination of a lifelong wonder—who is this girl who looks so much like me? What kind of connection will we make? What could life had been like? To some extent, there seems to me that there are no dividing lines to this story. My life, at least some long-felt undercurrent of it, had always been leading up to this point.

I arrived in Plymouth late, dropped off at a dark, eerie bus station. I routed my way to the hostel and began the trek, planning with my sister where we’d meet for drinks as I walked. The hostel entrance was in a dimly lit alleyway, just a faded sign over a locked door. I knocked loudly and a man came who quickly, clearly annoyed, informed me that there were no vacancies and shut the door. I frantically began to look for a last minute, affordable option. All I could find was a cheap Travelodge room (still overpriced) and, luggage in hand, jogged fifteen minutes over to it.

I was running a little late to meet up with my sister, but if I got the room quickly, I could still make it. It was not a luxury stay, with its brown wallpaper and sandpaper carpet. I sprinted out of the hotel and booked it to the bar we were meeting at, only a couple minutes late. Since I was wearing “trackies” (joggers) though, the bouncer informed me I’d have to change.

“Really? Even a guy as good looking as me?” The bouncer and three girls in line laughed.

“Sorry mate, not even with that amazing accent of yours.” All my powers of persuasion exhausted, I booked it back to the hotel, bitter and stunned that this little bar in this little town with a fifteen-by-fifteen-foot linoleum dance floor, of all places, would have a dress code. When I got to my room my key wouldn’t work. I dashed down the three flights of stairs to the front desk where I was told the key cards won’t work if they’ve been placed in a wallet. A slight design flaw, I’d say. So, I waited to get a new card.

Back up three flights of stairs, down three flights of stairs, and a five-minute run to the bar. When I finally got there, I was over thirty minutes late, again out of breath, and despairing that my first ninety-minutes in Plymouth had set a terrible trajectory of my weekend.

Aided by a few ciders the conversation slid on easy enough. Our lives were, at that moment, incredibly different. My life was overwhelmed with constant change, a revolving door of new places, new people, each day more unpredictable than the last. Hers was a steady run of little things, consistently bookmarking each week in a place that seemed to have changed only slightly since the Mayflower set off from it four-hundred years ago.

Still a small fishing town centered on a church, with a grand fortress overlooking a calm harbor, Plymouth seems like the place you go to retire, to clear your head, to get away from it all. It did not seem like the place a college student goes to see world, and my sister seemed to feel the same. I felt eager, even anxious, to make this long weekend something memorable, so we took a gamble—we booked last minute tickets to Bristol.

We walked Plymouth for the rest of the night, at one point paying two pounds each to see the local dance club: twenty-five college students dancing in schools of three to five, with about a fishing rod of length in between the groups. We weren’t there long. Plymouth after midnight was silent, the seagulls slumbering, only a few streetlights left on. Even the pigeons tip-toed so as to not disturb the peace as they scoured little crumbs off cobblestone walkways.

When I got back to the hotel, I called my roommates and then a good friend with the hotel wifi and talked about my worries. Life’s chaos doesn’t often worry me, I’ve come to accept it as inevitable, but this night was different. If life is a dice game today felt barely breakeven, if not a loss. Now I was doubling down. Things in Plymouth can only go so wrong, but in Bristol the risks were higher.

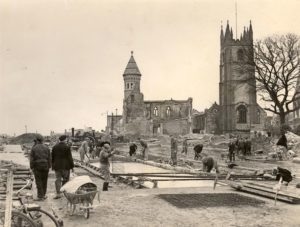

While my sister packed the following morning, I walked around Plymouth. The dominating sight in the Plymouth skyline, if it can be called that, is St. Andrew’s Church. Established in the 12th century, built up in the 15th, bombed in the 20th and reconstructed some years later with the word “resurgam” above the door, Latin for “I shall rise again,” the Anglican church stood as an impressive testament to Plymouth’s history. The rest of Plymouth seemed uninterested in any type of rising, however. Content to be nothing more than what it has always been, the only other sign of previous ambition I saw in the town was a placard declaring “second best fish’n’chips in the U.K.—2018.” The fish and chips were indeed incredible.

While my sister packed the following morning, I walked around Plymouth. The dominating sight in the Plymouth skyline, if it can be called that, is St. Andrew’s Church. Established in the 12th century, built up in the 15th, bombed in the 20th and reconstructed some years later with the word “resurgam” above the door, Latin for “I shall rise again,” the Anglican church stood as an impressive testament to Plymouth’s history. The rest of Plymouth seemed uninterested in any type of rising, however. Content to be nothing more than what it has always been, the only other sign of previous ambition I saw in the town was a placard declaring “second best fish’n’chips in the U.K.—2018.” The fish and chips were indeed incredible.

I ate them by the harborside and listened to gulls’ cry to the rhythm of clinking ropes and ship’s bells, with a pigeon and a bit of wine for company. I left plenty early to not miss the train, and rightfully so, since I missed the bus stop for the train station. It was about another fifteen-minute jog, once again with all my luggage, to the train. I was going to be a full-blown runner by the end of this trip, just not intentionally.

I made it with plenty of time nonetheless, finally having learned my lesson about leaving early. The train ride was England at its finest—sheep galore, rolling hillsides of green, and thickets of woods that must have been created by some set designer for a Robin Hood movie.

We got into Bristol just after sunset, with a short bus ride to the hostel we had booked. Keeping with tradition, I got us onto the wrong bus, or, more specifically the right bus headed in the wrong direction. God forbid I ever actually get anywhere smoothly. We remedied the mistake with a walk through Bristol at night, a criss-cross of graffitied alleyways and cracked sidewalks. Despite the fraught circumstances the walk felt promising.

Even when dimly lit Bristol is a city full of life. The slightest illumination reveals scores of street art endowing each street corner with a life of its own. It was on Bristol’s cracked streets that Banksy, along with many other respected street artists, got their start. Just a three-minute walk from city hall, when crossing a bridge, you’ll walk by Banksy’s “The Well-Hung Lover,” a multi-million-dollar piece of art if you’re paying attention. Such surprises abound in Bristol, products of its progressive culture intermingling with a rich history.

Even when dimly lit Bristol is a city full of life. The slightest illumination reveals scores of street art endowing each street corner with a life of its own. It was on Bristol’s cracked streets that Banksy, along with many other respected street artists, got their start. Just a three-minute walk from city hall, when crossing a bridge, you’ll walk by Banksy’s “The Well-Hung Lover,” a multi-million-dollar piece of art if you’re paying attention. Such surprises abound in Bristol, products of its progressive culture intermingling with a rich history.

A sense of rebellion and counterculture attitude is woven into Bristol’s history as deeply as the city’s many canals and waterways. Bristol’s port is the biggest and closest to the Americas, which made Bristol a sea-trade capital in the 1700’s, and simultaneously the capital to almost all of pirate culture. It’s here that a young Edward Teach, long before he ever became Blackbeard, drank at the Hatchett Inn, and at these docks that Anne Bonny eloped and fled to the new world, and here, at the Llandoger Trow, Daniel Defoe sat listening as a recently returned castaway told the story that would become Robinson Crusoe, and not even a five minute walk away, a hundred years later, Robert Louis Stevenson would begin writing Treasure Island in a small room in the upstairs of a pub.

A sense of rebellion and counterculture attitude is woven into Bristol’s history as deeply as the city’s many canals and waterways. Bristol’s port is the biggest and closest to the Americas, which made Bristol a sea-trade capital in the 1700’s, and simultaneously the capital to almost all of pirate culture. It’s here that a young Edward Teach, long before he ever became Blackbeard, drank at the Hatchett Inn, and at these docks that Anne Bonny eloped and fled to the new world, and here, at the Llandoger Trow, Daniel Defoe sat listening as a recently returned castaway told the story that would become Robinson Crusoe, and not even a five minute walk away, a hundred years later, Robert Louis Stevenson would begin writing Treasure Island in a small room in the upstairs of a pub.

Though I wouldn’t know any of this until the following day when we went on a walking tour of Bristol, I could feel it that night as we made our way to the hostel. Perhaps it’s hindsight bias, or maybe it was the ambiance of timeworn streets combined with avant-garde street art, but there was something about Bristol from the start that assured me this weekend would be memorable.

And it was.

The city center was amazing. Our first night began with drinks and snacks on a boat moored on one of the canals, then took us to a game bar with darts, shuffleboard, and pop-a-shot, where, in true big brother fashion, I beat my sister in every game to her utter frustration. It seemed the universe, or fate, God, or whatever that’s out there that is larger than me was on my side, because I have no idea how I kept winning, though that’s not what I told my sister.

From there to a dart club, from there to a jazz bar, my favorite I’ve ever been to, a multi-colored hideaway with Great-Gatsby-if-Gatsby-was-a-hippie décor and an amazing band, and from there to a packed dance floor. In the morning came cathedrals and art museums, and the following night brought more pubs and clubs. On our last night together, we walked Bristol peacefully again, just us, a few cans of spray paint of our own, and some snacks and drinks from Tesco’s.

We talked about childhood. Our own to begin with but in the end just childhood. That weird, uncomfortable, rebellious period of our lives that binds us all, but which binds me and her more than most, not because we shared one, but because we didn’t. It is at times like this I sorely wish I was a better writer. I had always thought it was strange, to have a sister I was tied to by blood, but not by experience. She is the only person in the world that knows what my life could have been, what it might have felt like. Perhaps, to some extent, I am the same for her.

For the one thing that connects us, there is so much more that doesn’t, yet that is never how it has felt. I never knew what to make of that. So, we sat on the steps of Bristol’s council house in the moon-shadow of a cathedral trading stories of teenage rebellion, parents so frustrated veins were popping from foreheads, the little teenage traumas of misplaced pimples and a few of the bigger ones, and I felt both understood and understanding, and the overwhelming comfort, relief, and love that comes from that. I felt like a big brother.

That would be a great place to draw the dividing line, close the curtains on this play, but the story doesn’t really stop there. We ran out of drinks and snacks and decided to walk to the closest bar. At the door a man with what I’m guessing is a Bangladeshi accent. checked our American I.D.’s and said, “Americans! I love your movies. Every time I watch Forest Gump I cry, ‘Life is a box of chocolates,’ yea? So good. Oh, and The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly! I love it! It is great to see how Americans live. Thank you!” Truthfully, he went for almost five-minutes, pulling us to the side of the door while his co-worker helped other people in.

When he finished, dumfounded, we told him, awkwardly, that he was welcome? And then went in. However, little did we know that our American stardom was just beginning because, unbeknownst to us, we had just walked into a sports bar fifteen minutes before the Superbowl started. It truly seemed like the universe, or fate, or whatever helped me win at all those bar games was speaking when in this bar we ran into multiple people wearing, of all things, Seahawks jerseys, an homage to the city that both my sister and I were raised in. It was the perfect consummation to our conversation. It seems that traveler’s luck runs in the blood.